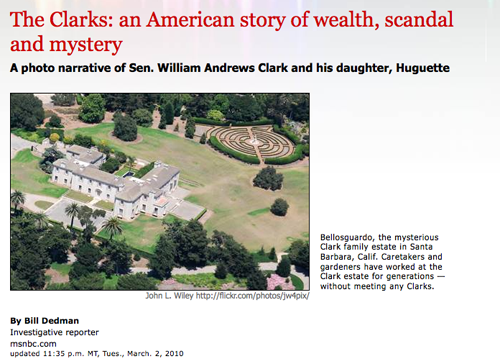

Until recently, very few people realized that Huguette Clark, the daughter of Montana copper king William A. Clark, is still alive. She’s reportedly almost 104, is fabulously wealthy and has no heirs. She owns mansions in Connecticut and California, vacant for many decades, and other property worth $200 million, according to a story published on MSNBC in early March.

For Montanans, the news about Huguette was startling, and revived the oft-told stories of Clark, the robber baron who left little for the state where he made much of his wealth.

Yet even the story’s author, ace investigative reporter Bill Dedman, doesn’t know where Huguette is, although he spent two months trying to track her down, schmoozing with doormen and poring through archives and databases and photo archives.

That’s OK by Dedman, however, because the dramatic story that he put together about Huguette and her Croesus-like father, told in a simple slideshow format on the Web, attracted more than 78 million page views: More than Michael Jackson’s death — almost as many as the initial coverage of the Haiti earthquake. (view slideshow). It also elicited about 500 e-mails to Dedman, far more than he’s received for any other story, including “The Color of Money,” his Pulitzer Prize-winning stories in 1988 for the Atlanta Journal & Constitution on redlining, or discriminatory home loan practices by area banks.

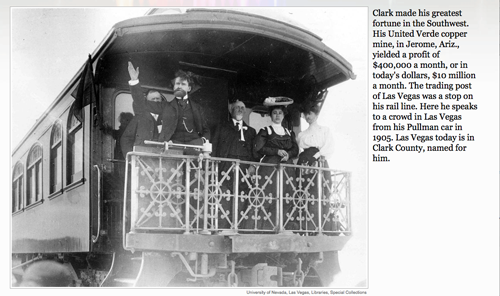

The 47-slide show, pictures with extended captions (also on a separate webpage), poses the mystery of the vacant mansions then goes back in time to tell the fascinating back story of Clark, how he accrued his wealth, his infamous attempt to buy a U.S. Senate seat, how he spread his wealth around in New York, Europe and other places besides Montana, the birth of Huguette to his young second wife, Anna, and the tragic arc of Huguette’s life.

It is a pure exercise in linear storytelling, and simple. No audio, no video, just words and photos. And therefore unusual in an online setting where hyperlinks make it easy to tell a story in an interactive way that encourages readers and viewers to choose their own path through the story.

That approach might work well for, say, a feature story about a musician, Dedman notes. You go through one door and sample the discography, then through another door and watch a video clip, and another door to read a biography or an anecdote.

But “I’m not persuaded that non-linear storytelling is necessarily the way to go,” Dedman said. “Viewers and readers like to be told a story which has a beginning, middle and end. [Especially] when you’re being introduced to characters people don’t know, I think it’s the responsibility of the writer to take your hand.”

“It's all a little abstract — empty houses, old women — but with the photos you can say ‘Look here it is, Clark, and here is his daughter, and she's still alive,'" Dedman told the Montana Standard.

Dedman and the MSNBC team he works with arrived at that linear approach almost by accident. Following his nose from his home in Connecticut, Dedman began accruing photos from archives and other sources, including the University of Montana, intending to write a story that would be published on the MSNBC website. To present his results in a conference call with other team members in Redmond, Wash., Dedman used an automated slide show program developed for MSNBC. A photographer suggested publishing the story just like that—as a slideshow.

“I was a little reluctant at first,” Dedman recalled. He thought a slideshow would cramp his writing. But he took to it and started advocating it, arguing that “even if you give up a little in the storytelling, a lot more people will pay attention.”

Writing to pictures, and writing tight, introduced a certain discipline to the process that Dedman admits he found a bit frustrating at times, though ultimately worth it.

“I had to give up some things,” Dedman said. “A writer might be tempted to add a little more about that building, or tell an anecdote that someone who had visited the house had shared.”

A perfect example is a 1907 Mark Twain essay crucifying Clark, which goes on for several pages. Dedman couldn’t quote more than a snippet of Twain’s prose (“He is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag…”), and he didn’t have room to explain that Twain had profited enormously from financial deals engineered by Clark’s arch-rival, Henry Huddleston Rogers. Instead, that parenthetical but rich detail had to go on the sources page, the digital footnotes.

Yet the story still comes to almost 2,800 words, as much as Dedman would have written in a text version illustrated by just a few photos. One advantage of the slides-only show, without audio or video, is that “people can go through it at their own pace; they’re not trapped by the pace of my voice,” Dedman said. While MSNBC could easily have done a video version, complete with Ken Burns-like pans and zooms on still photos, “it didn’t feel like it would profit us much,” Dedman added. Besides, he noted, a lot of people are viewing the piece at work, where a silent show is easier to view.

A photo sideshow typically presents a much lower barrier to entry by readers than a long text piece, noted Steve Myers, managing editor of Poynter Online. “People know the smaller the scrollbar gets, the longer it’s going to take to get through the piece, and they may say, ‘Wow, I don’t have time for this,’” said Myers, who posted a piece on Dedman’s story.

The story’s popularity on the Web took Dedman and others by surprise. More than 78 million page views works out to about 1.7 million people calculated[J1] to have clicked or scrolled through to every slide. About 85,000 people went to the sources page. Once the story was off MSNBC’s cover, page views naturally went way down, showing the typical “long tail” of once-popular online stories, with occasional bumps when the subject is back in the news. But then, that’s nothing new in an industry with a long tradition of providing bird-cage liner.

Still, the Huguette story and its linear form “suggests some middle ground” for future storytelling between non-linear pieces and text stories. “It’s another way to tell a story when you have a rich selection of photos,” Dedman noted. “But it’s not as if you’re going to tell all stories through slideshows.”

What makes this story so compelling, Myers said, is the underlying tale and the effective use of images to tell that tale, cool stuff like old passenger manifestos and the insides of those vacant houses.

The key to using multimedia, Dedman believes, is to be flexible, and to achieve proficiency in collecting audio, video and the written word, and then in knowing which medium or combination of media to use for best effect.

If you figure it out, you may have the kind of success Dedman achieved with the curious tale of William and Huguette Clark.

Whether Huguette herself has seen the story is not known. Her attorney, William Bock, said her mind is clear. He said he frequently receives instructions from her—by phone.